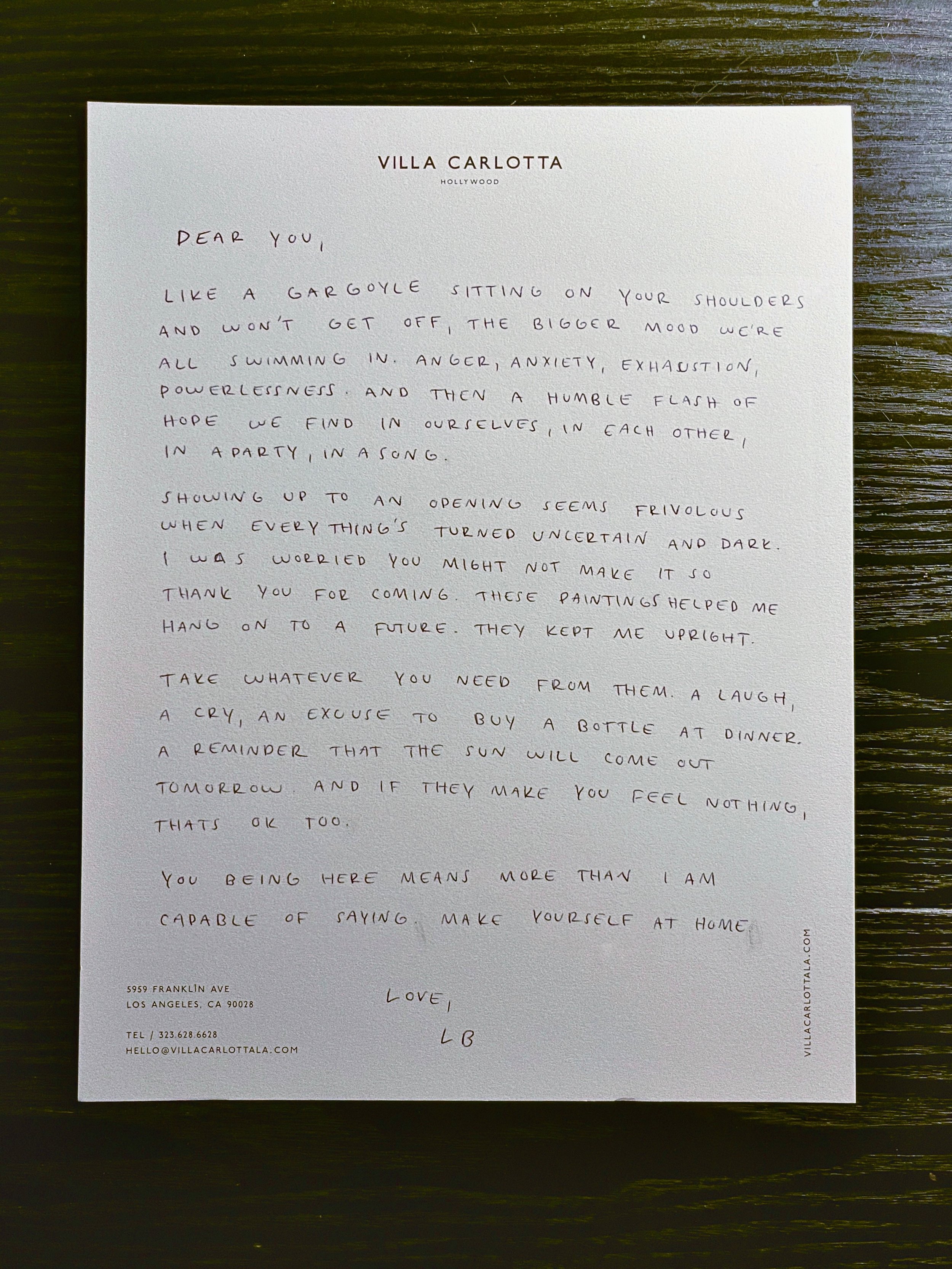

LEONARD BABY

Resting Babyface

Opening Sunday: February 25th, 7-9 PM

VILLA CARLOTTA

5959 Franklin Ave

Los Angeles, CA 90028

February 25th - March 10th, 2026

LEONARD BABY

Resting Babyface

Opening Sunday: February 25th, 7-9 PM

VILLA CARLOTTA

5959 Franklin Ave

Los Angeles, CA 90028

February 25th - March 10th, 2026

Appointment Only